do it (2013-) – Exhibitions – Independent Curators International

“Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, do it began in Paris in 1993 as a conversation between Obrist and the artists Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier. Obrist was concerned with how exhibition formats could be rendered more flexible and open-ended. This discussion led to the question of whether a show could take “scores,” or written instructions by artists, as a point of departure, each of which could be interpreted anew every time they were enacted. To test the idea, Obrist invited 12 artists to send instructions, which were then translated into 9 different languages and circulated internationally as a book.

Nearly 20 years later after the initial conversation took place, do it has been featured in at least 50 different locations worldwide, including Australia, China, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Costa Rica, Slovenia and Uruguay. The driving force behind the exhibition is aptly summarized in the words of Marcel Duchamp, who states that “art is a game between all people of all periods.” He is only one of several predecessors to have shaped the modus operandi of this exhibition, which also draws from Conceptual and Minimalist art of the 1960s and 1970s as well as Fluxus practices. Each do it exhibition is uniquely site-specific because it engages the local community in a dialogue that responds to and adds a new set of instructions, while it remains global in the scope of its ever-expanding repertoire. This also means that the generative and accumulative aspects of do it’s ongoing presentation are less concerned with notions of the “reproduction” or materiality of the artworks than with revealing the nuances of human interpretation in its various permutations and iterations. In this way, do it is able to bridge the gaps between the temporalities of past, present and future.”

Source: do it (2013-) – Exhibitions – Independent Curators International

Do It (1997-) – Exhibitions – Independent Curators International

“do it began in 1993 with a discussion among Christian Boltanski, Bertrand Lavier, and myself in the Café Select, Paris. Both artists have been interested in various forms of instructional procedures since the early 1970s, and that evening they spoke of the instructions contained within their own work. Since the 1970s, Lavier has made many works that contain written instructions in order to observe the effects of translation on an artwork as it moves in and out of various permutations of language. Boltanski, like Lavier, is also interested in the notion of interpretation as an artistic principle. He thinks of his instructions for installations as analogous to musical scores which, like an opera or symphony, go through countless realizations as they are carried out and interpreted by others. From this encounter arose he idea of an exhibition of do-it-yourself descriptions or procedural instructions which, until a venue is found, exist in a static condition. Like a musical score, everything is there but the sound.”

Source: Do It (1997-) – Exhibitions – Independent Curators International

Jimmy Robert, Untitled, 2005

“Jimmy Robert is an artist who lives and works in Berlin. Robert’s practice ranges across performance, film, photography, works on paper, and writing. His work subtly explores the intersections between art history, representation and subjectivity.

Robert often reconsiders crucial moments from avant-garde art history, questioning their capacity to reflect the political complexities of lived experience, especially from a Black, queer perspective. Figures as varied as Stanley Brouwn, Marguerite Duras, Hokusai, Georges Balanchine, Bas Jan Ader and Yoko Ono have served as points of departure in previous works.

Notable among his recent performance works is Joie Noire (2019), part of a series reflecting on the legacy of Robert’s friend and frequent collaborator Ian White. Using a collage of textual and musical material, this two-person performance addressed the racial and sexual politics of the AIDS crisis and the aesthetics of art, music and dance in the 1980s. ”

source: https://glasgowinternational.org/artists/jimmy-robert/

“Robert typically uses photographic portraitureas a starting point for his works on paper, gently breaking down divisions between two and three dimensions, image and object. In some cases Robert uses found photographs that he tears, collages, tapes, and crumples before digitally scanning them and pinning them to the wall. In other cases, Robert takes new photographs in his studio and crams them into wooden boxes or arranges them on the gallery floor. Extending into the space of the gallery, these works create a relationship to the viewer’s body while underscoring a sense of impermanence. Likewise, Robert’s sculptures are either made from wood-based materials or give the illusion of paper forms and often play with notions of value and durability.

Robert’s films and videos convey a sense of the ordinary in their scale, subject, and material. Broadly inspired by the French New Wave, the artist is also deeply influenced by feminist filmmakers such as Marguerite Duras and Chantal Akerman. Of a similarly intimate register, Robert’s dance and performance works value gesture and chance over elaborate choreography, referring to Fluxus and the Judson Dance Theater.”

source: https://mcachicago.org/Exhibitions/2012/Jimmy-Robert-Vis-A-Vis

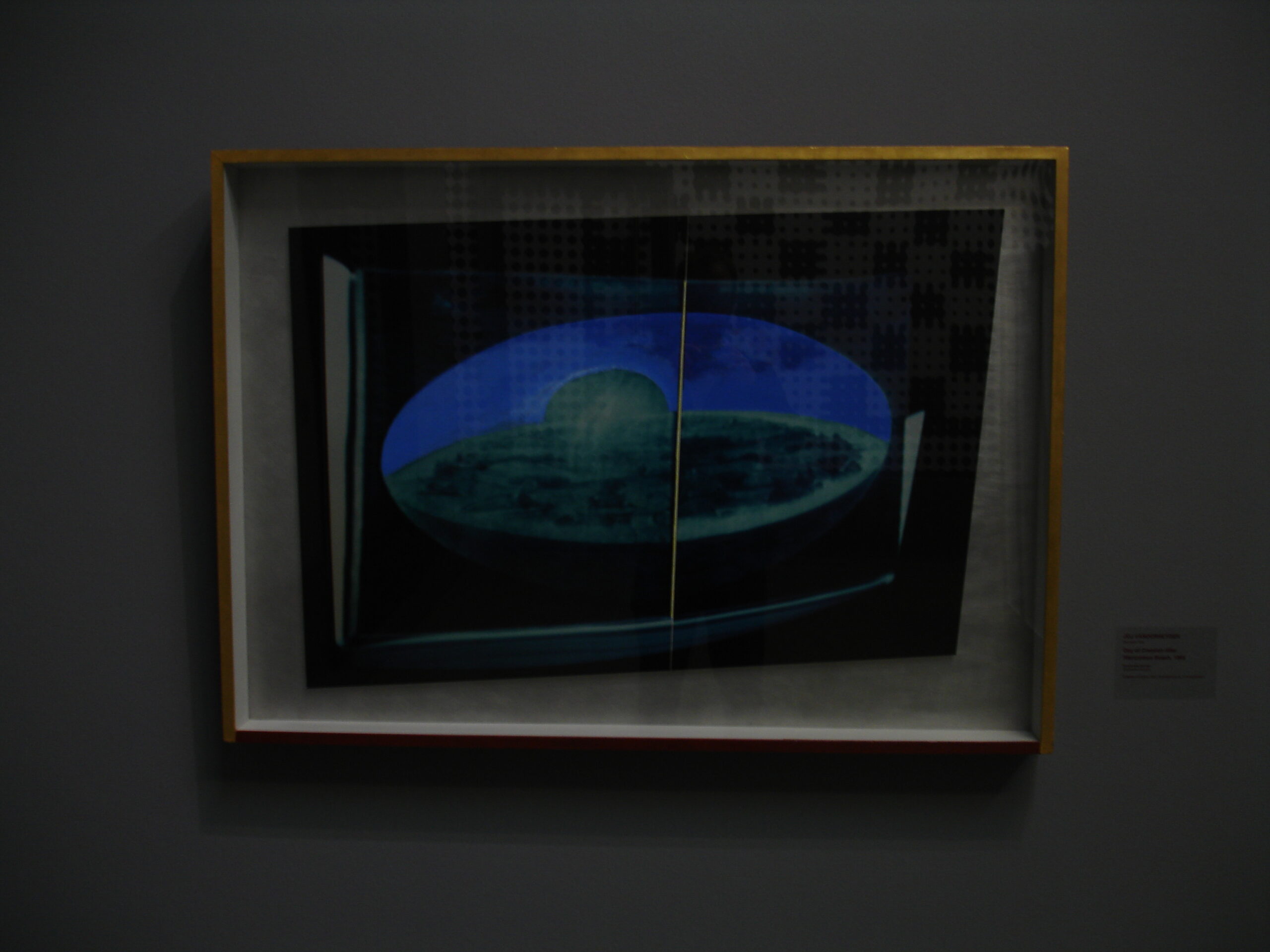

Nebula Humilis, 2011 by Lola Guerrera

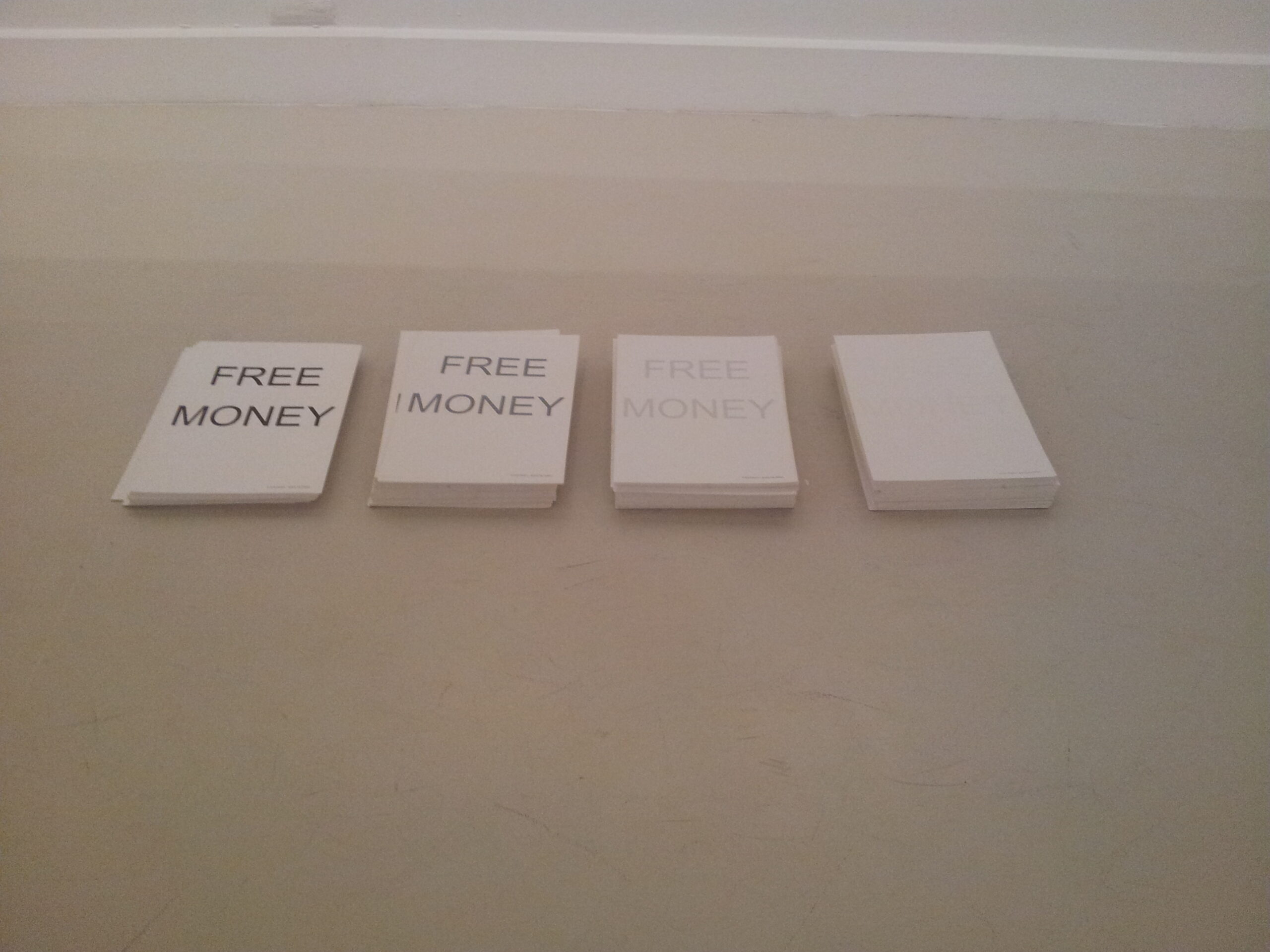

‘Creative Inquiry Preparing an Educated Electorate with the Will of Social Justice rather than Simply Self-Interest’-2013 by Jesús Palomino at the CAC Málaga, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Málaga

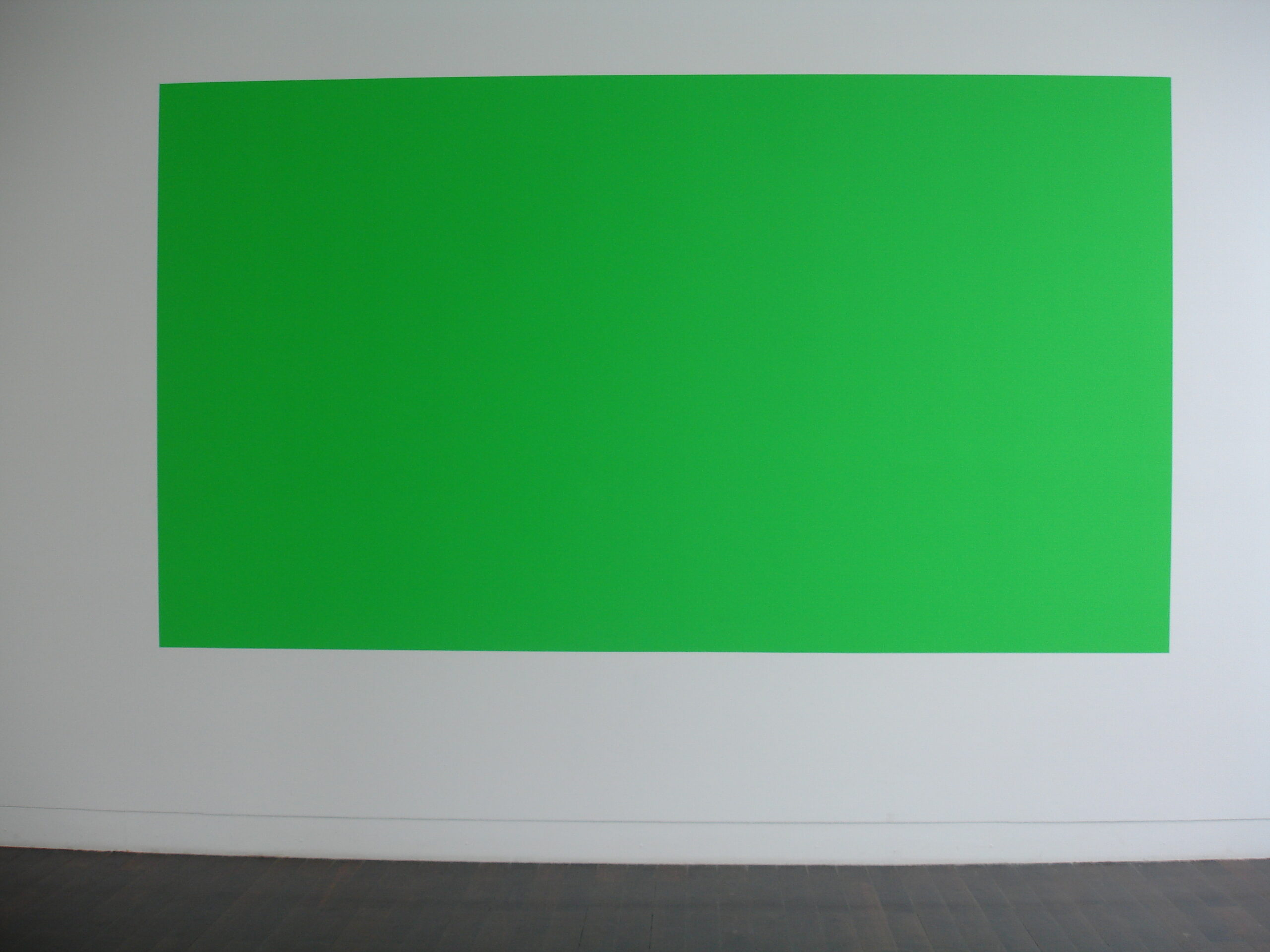

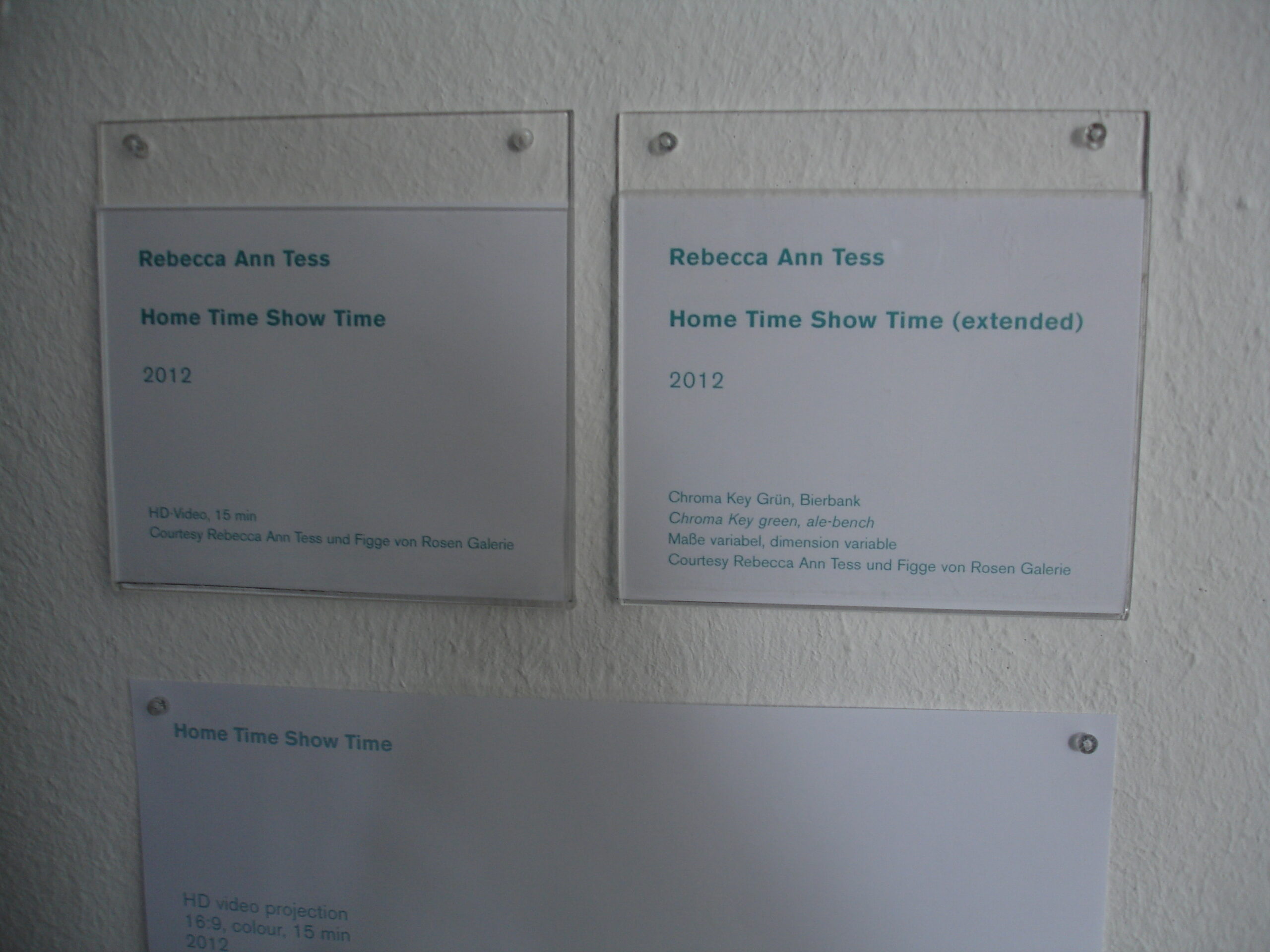

Rebecca Ann Tess – Home Time Show Time, 2012